After much work, Winchester City Mill was fully restored to working order in 2004. The pristine condition of this flour mill belies its great age. It was pre-Covid lockdown when I last visited before I started Roland’s Travels. The mill came back to mind, and I checked my photo album and realised I should share this with you.

Winchester City Mill on the River Itchen

Winchester City Mill draws its power from the River Itchen and has done so for over one thousand years. The mill, originally known as Eastgate Mill until 1554, is recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086. However, records show that the mill was there well before 1086. Winchester Cathedral records go back to 932, which mentions Eastgate Mill. In 989, Queen Elfrida passed the mill to Wherwell Abbey. Dendrological measurements of some of the present mill timbers indicate they are from the 11th Century.

It’s lovely to see this mill survive when thousands have long disappeared. It is even better to know that this flour mill still works and is producing flour on a small scale for demonstration purposes, but it works. The mill can produce 20-30kg of flour per hour.

In 1774 the mill was rebuilt by James Cook, a tanner. In 1820 the Corporation sold the mill to John Benham. It continued as a mill until the 1900s. During World War One, the mill was used as a laundry. The mill was offered for sale in 1928 and was purchased by a group of benefactors who wanted to ensure it survived. The benefactors gave Winchester City Mill to the National Trust. Moving on and in 1931, the mill was leased to Youth Hostels Association as a hostel, which continued until 2005.

Watching the mechanical process of turning water power into motion is always fascinating, akin to looking at the parts of a mechanical clock, although the mill's cogs turn far quicker. From start to finish seeing a product made without computers or electricity and in a way that has been used for centuries is genuinely satisfying. The mill uses nature, water for power, gravity to move the product through the manufacturing process, wood and some metal for the machinery and stones for the grinding. A truly low-impact method on the environment and today would be described as environmentally friendly and sustainable.

Modern industrialisation went for scale, and thousands of mills could be replaced with very few modern ones. Today, many might question which is the better system.

When visiting places like Winchester City Mill, it’s good to reflect on how life must have been for the millers all those centuries ago. A time when much of the work done revolved around the seasons, the amount of daylight and weather conditions. It would have been a hard life, yet, in many ways, so much better than the stress-filled environment many have to work in today. Would you have liked to work with these older methods of production? Please drop me a comment in the comments section.

I thoroughly enjoyed the process being explained by the volunteers, and in the videos above, you can get a feel for the authenticity of this mill. The National Trust has done a great job keeping the miller's skills alive for anyone to come and observe.

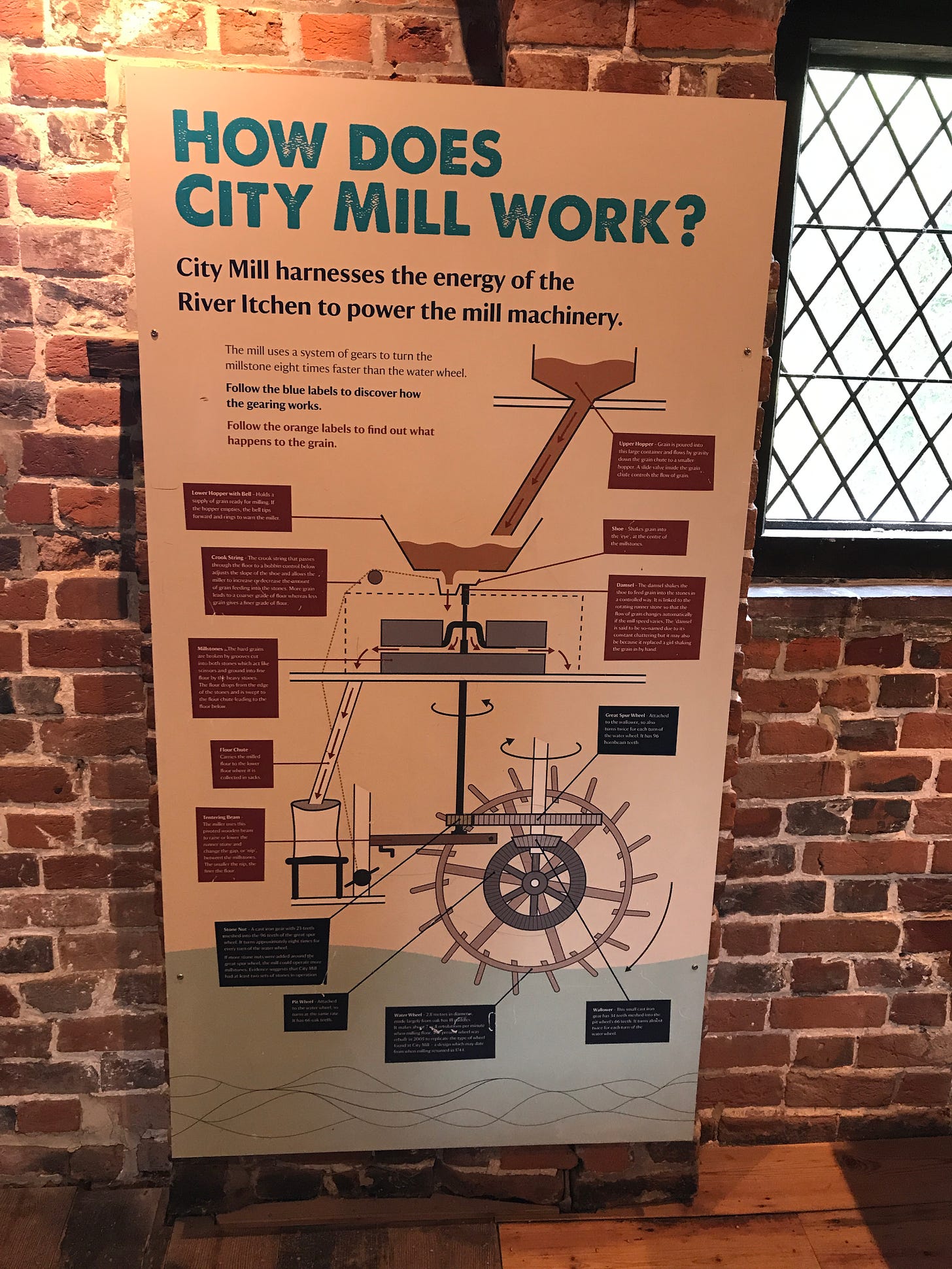

How does the Winchester City Mill work?

The process of milling starts when the grain is hoisted to the top of the mill to allow gravity to play its part. The miller empties the sacks of grain down the wooden chute into the hopper above the millstones. What is known as the shoe under the hopper shakes the grain into the centre of the top runnerstone.

The damsel protrudes from the centre of the stone and rotates at the same speed as the millstone. This strikes the shoe and causes it to shake. With the increase in speed of the mill, so does the flow of the grain.

The bell, fixed to the horse, which you can see in the opening video, warns if the hopper becomes empty. If this were to happen, the millstones would run without grain and flour between them, leading to rapid wear and damage—the grain and flour act like the lubrication of oil in car engines.

The grain passes between the millstones. The top stone is the runnerstone, and the lower is the bedstone. It is the passing of the grain between these stones that makes the flour. The stones will rotate at 60 revolutions per minute or above to mill high-quality flour. That’s a fairly fast speed created by the gearing of the cogs from the water wheel.

The final process is to bag the flour, which has passed down a second chute to the lower floor, where it is collected in sacks. All that remains is for it to be delivered to the bakers to produce some lovely bread or cakes. Did someone mention cake? Oh yes, there is a cafe at Winchester City Mill. It would be rude not to try out the cake, wouldn’t it?

If you visit the mill, check before you go for when there are flour-making demonstrations. The mill wheels keep turning but not flour production. Here is the National Trust website.

When you visit, plenty of information boards and videos help you understand the milling process.

Nature is also a focus, as the river has otters and many interesting birds. You can look at the Otter Cam and see what it has captured of the otters’ activity. At the rear of the mill, there is a lovely garden running alongside the River Itchen. See how many species of birds you can spot.

The City of Winchester is a place that I must return to for more exploration. It was once the capital city of England and was made such by King Alfred in 871. This will go onto my 2023 project list, so please become a free subscriber, and you won’t miss out!

Share this post