If you’re a regular reader of Roland’s Travels, you will have read that I often refer to a town or village’s history, and note if these places are recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086.

Why was the Domesday Book written?

Following the Norman conquest by King William l (William the Conqueror) in 1086, the king wanted to know more about the land he was now reigning over. He mainly wanted to know so he could raise taxes to fight the Danes (Vikings) who were causing trouble for his new country. The tax raised was called Danegeld.

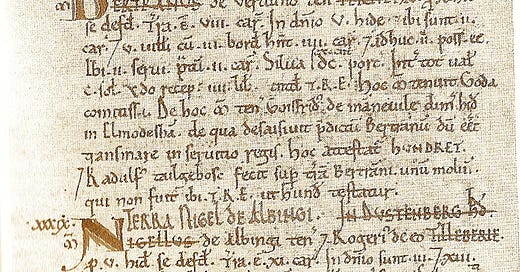

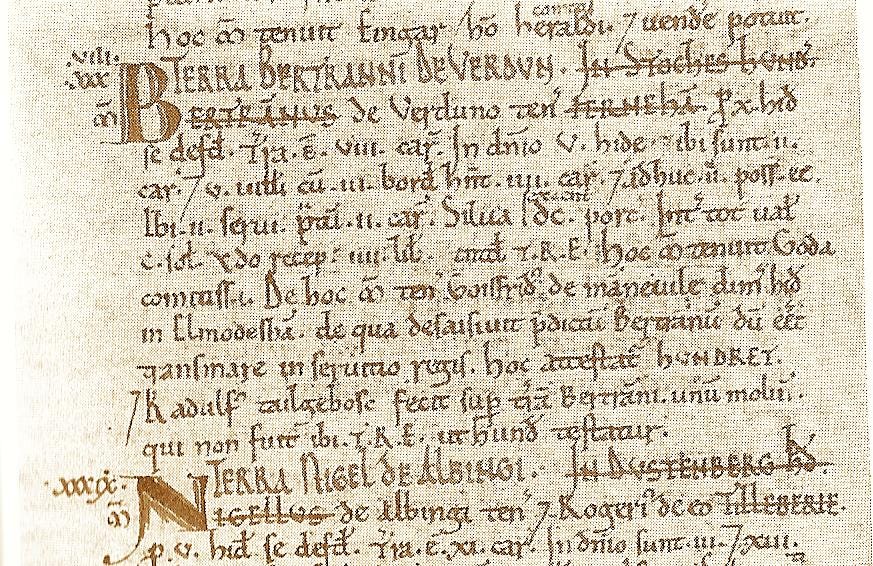

The survey was commissioned in December 1085. England was divided into circuits, seven in total. Three or four commissioners were assigned to each circuit. They all carried a set of questions to be asked to a jury of representatives in each area. The jury was made up of barons, noblemen and villagers. The information was recorded in Latin.

The survey covers England and a few places in what is now Wales. The Scottish border at the time was south of the rivers Ribble and Tees.

King William l wanted to know not just the value of land and who owned it then but what it was like before 1066. The same questions covered three periods, pre-1066, 1066-1085, and 1086. See below to see what the questions were.

The survey was not a population count. It counted heads of families, not wives, children, or slaves. It also excluded major cities such as London and Winchester. The population tallied in the Domesday Book is 268,984. England still would have had a very low population density compared to today.

This was written in The Ely Inquest, a contemporary publication at the time

"...They inquired what the manor was called; who held it at the time of King Edward; who holds it now; how many hides there are; how many ploughs in demesne (held by the lord)and how many belonging to the men; how many villagers; how many cottagers; how many slaves; how many freemen; how many sokemen; how much woodland; how much meadow; how much pasture; how many mills; how many fisheries; how much had been added to or taken away from the estate; what it used to be worth altogether; what it is worth now; and how much each freeman and sokeman had and has.

All this was to be recorded thrice, namely as it was in the time of King Edward, as it was when King William gave it and as it is now. And it was also to be noted whether more could be taken than is now being taken."

The last line above is interesting. Can more money be collected? Not much has changed!

The Domesday Book comprises two books, Little Domesday and Great Domesday. Little Domesday comprises just three counties but has more pages, 475. It is written in unabridged form. The Great Domesday Book has 413 pages, and the records are abridged. This book is written in Latin on sheep-skin parchment. Red ink is used for the county titles, and the main text is in black. Both books are amazing survivors and are the oldest government record held in the National Archives.

It wasn’t originally called the Domesday Book. This title was given in the late 12th century. The people regarded the listing as something Biblical akin to the Great Judgement in the Book of Revelation. They associated this with doomsday (the Final Judgement). Domes is the Old English spelling of doom.

Can you read the Domesday Book?

The good news is we can read the Domesday Book online with English translations. You can use the search box to see if your town or village is included.

Click here to read the Domesday Book online at Open Domesday

I find it fascinating that we have so many written documents to consider when we look back in time. Do check out the online version - click the above link and then click on the photo of the book to search for the text of a place you’re interested in.

Thank you for reading. If you’re not a free subscriber to Roland’s Travels, use the box below. You will not be spammed! Your comments, likes, and shares are always appreciated.